Brigadier General (ret.) Chuck Yeager is out of date when it comes to Air Force flight testing. Nowadays, an Air Force flight test pilot has at least a bachelor’s degree in engineering, and the majority have master’s degrees. In contrast to today’s test pilot schooling, Yeager did not graduate or attend college.

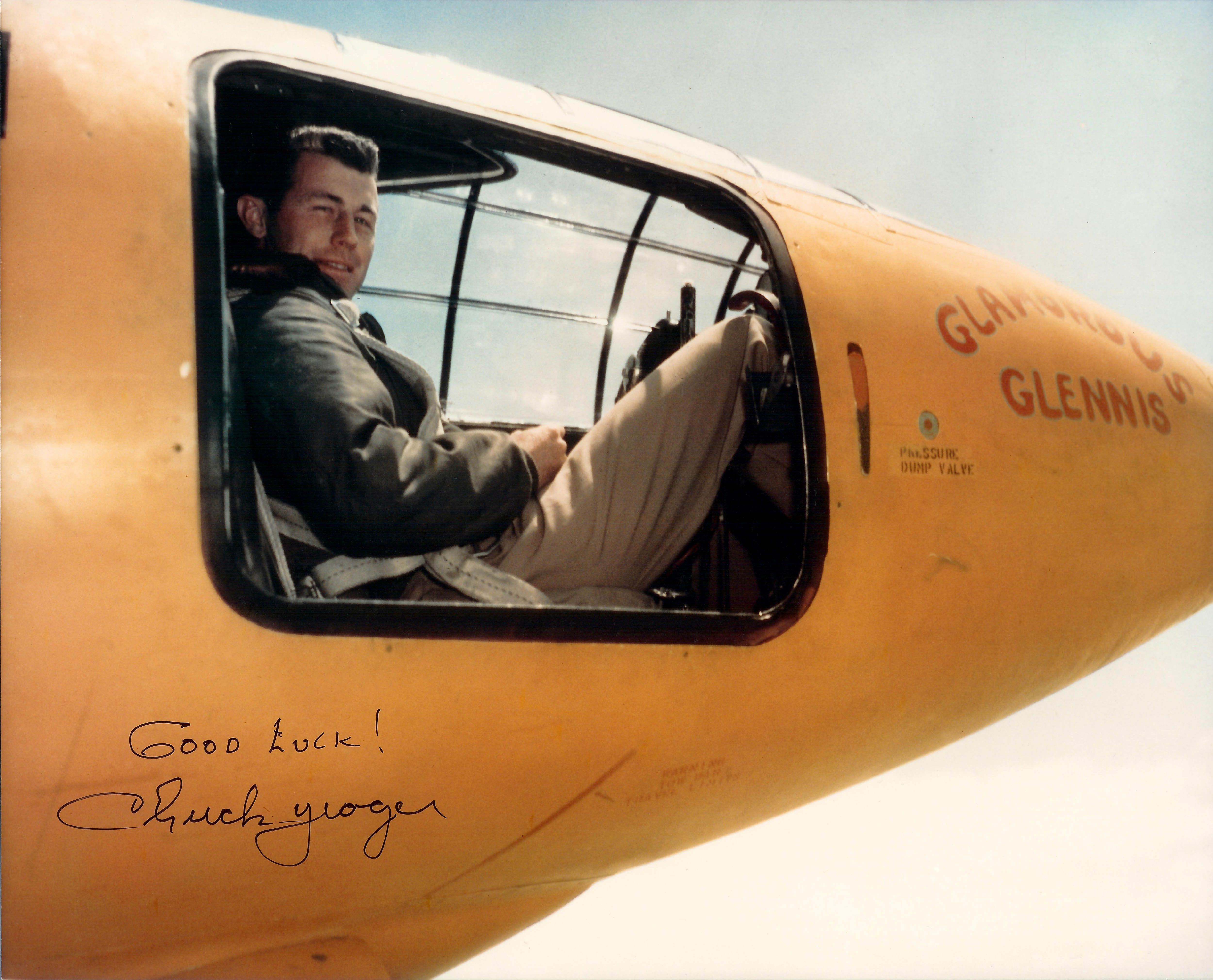

On October 14, 1947, Charles (Chuck) Yeager broke the sound barrier for the first time in history.

In the twenty-first century, Yeager would be ineligible for the Air Force’s pilot test program or entry-level aviation schools.

During Chuck Yeager’s time, the majority of military pilots were not college graduates. Yeager never considered not having a college degree to be a barrier. He was often described as a natural-born pilot.

Despite having no formal engineering training, Yeager was often referred to as a “intuitive engineer.” He could diagnose a problem in flight and decide on a course of action.

According to Chuck Yeager’s friend and fellow test pilot, Jack Ridley, “Yeager flew an airplane as if he was an integral part of it, and that his ‘feel’ for the plane was instinctive.”

In test pilot vernacular, Yeager was a terrific “stick n’ rudder man.” Another way to define Yeager’s piloting abilities was his ability to “fly by the seat of his pants.”

“Perhaps Chuck can fly without using the elevator. “Maybe he can get by with just the horizontal stabilizer.” This talk centered on Yeager’s near-fatal disaster during a Bell X-1 test flight the previous day. They were discussing solutions in case further issues arose during the next test flight. The Bell X-1 design engineers had already weighed in on the elevator’s freeze-up. Unless the X-1 project manager put everything on hold for a few months and instructed the engineers to come up with a design adjustment, Yeager and Ridley would have to devise some workarounds that they could test in-flight if required.

The preceding example revealed that test pilots were paid to take risks, and that when things do not go as planned, a college degree is less significant than seat-of-the-pants flying abilities.

General Yeager’s Early Career

Please view the embedded video for three minutes before continuing. It’s a good start.

Gen. Yeager was born in West Virginia in 1923. He graduated from high school in June 1941 and joined the Army Air Force three months later. He was trained as an aircraft mechanic, but he applied and was accepted into the Flying Sergeants Program a year later. He completed pilot training and was promoted to officer. Yeager departed for England in November 1943.

Yeager flew the North American P-51 Mustang during his deployment to the European Theater of Operations. His squadron was the 363rd Fighter Squadron of the 357th Fighter Group. Yeager’s 363rd FS was one of three units assigned to the 357th FG. They were all stationed at RAF Leiston for their ETO assignment.

Yeager became an expert P-51 pilot. During his many sorties escorting bombers into Germany, he earned the title of fighter “ace” by shooting down six Messerschmitt 109 fighters—five of them came in a single day! A month later, he defeated five additional Germans, including four Focke-Wulf 190s, all in one day.

- This Me 109 was shot on takeoff in May 2022 as part of a warbird airshow.

- This Fw 190 was spotted at a 2015 airshow in Ypsilanti, Michigan.

General Yeager participated in combat in WWII, Korea, and Vietnam. His military service lasted 34 years. He received the following medals:

- Presidential Medal of Freedom.

- Air Force Distinguished Service Medal; Army Awards include the Distinguished Service Medal,

- Silver Star (twice), and Legion of Merit (twice).

- Distinguished Flying Cross (3)

- Bronze Star with V (Valor) Device

- Purple Heart Air Medal (10)

- General Yeager received the Air Force Commendation Medal for his work outside of military combat duties.

When Yeager’s European war service finished, he returned to America. While many of his fellow Air Force officers chose to be discharged to have a family or attend college, the General chose to remain in the Air Force.

His wife was expecting their first child, so it seemed sense for him to be stationed near the town where they grew up in West Virginia. The closest choice was Wright-Patterson Air Force Base in Dayton, Ohio.

Given the lack of interstate roads at the time, driving to West Virginia took around four hours.

When Yeager transferred to Wright-Patterson in 1946, little thought was given to the position he would be assigned. It was actually quite fortuitous. Colonel Albert Boyd directed the Aeronautical Systems Flight Test Division at WPAFB.

Boyd was searching for a fighter test pilot. Colonel Boyd transferred Yeagar to Edwards Air Force Base’s flight test center in 1947. The historic supersonic Bell X-1 test flight would take place later in the year.

Chuck Yeager possessed a strong sense of duty. He said:

“It is your responsibility to fly the plane. If you die in it, you’ll have no idea what happened. Duty is paramount. It’s that simple if you’re a military man. You do not say, ‘I’m not going to do that because it’s unsafe.’ If it is your responsibility to do so, that is the way it is.”

Today’s flight testing differs from what it was in 1947. When Yeager first arrived at the flying test center, he was still a Second Lieutenant.

Wartime promotions were only temporary for many officers during World War II, including Yeager, and they would revert to their permanent rank after the war ended. This happened to Yeager, a temporary Captain.

Yeager was promoted to First Lieutenant two months before his famous X-1 flight. It was even more surprising that Yeager was just 24 years old, given his status!

Breaking Mach 2.

Until the Goldwater-Nichols Defense Reorganization Act of 1986, there was no mechanism in place to assure that career officers were assigned to at least one joint billet during their careers. Taking it a step further, the service branches did virtually little collaborative work.

This was never more true than during flight testing at Edwards. The Navy, Air Force, and NACA (NASA’s forerunner) were all carrying out their own flight test projects.

NACA hired the test pilots and engineers. Scott Crossfield and Slick Goodlin were the Navy’s favored test pilots during flight testing at Edwards. These pilots had a natural competition with the Air Force’s most popular pilots, Chuck Yeager and Jack Ridley.

Ever since Yeager broke the sound barrier in 1947, testing resources have been focused on breaking Mach 2. Crossfield and Goodlin flew the Navy-sponsored Douglas D-558-2 Skyrocket, whilst Yeager’s team flew the Bell X-1A for the Mach 2 test project.

The Bell X-1A was not truly a “A” version of the X-1. It had a similar outward appearance to the X-1, but it was much larger and had a completely different engine.

By 1953, both efforts had moved closer to Mach 2.

Scott Crossfield accomplished the accomplishment on November 20, 1953, in a Douglas D-558-2. Crossfield had barely surpassed Mach 2. Not to be outdone, Yeager’s team began preparing to break Crossfield’s record with the new X-1A.

After several X-1A flights, they gradually increased their speed to Mach 2. On December 12th, Yeager broke Mach 2, reaching a speed record of 2.44! Making matters worse for Crossfield’s team, the organizers of the 50th Anniversary of Flight Celebration, which was slated for December 17, 1953, intended to reward Crossfield for being “the fastest man alive.” The honor was a letdown after Yeager’s Mach 2.44 flight five days earlier.

The conclusion of Yeager’s extraordinary flight test career

Chuck Yeager’s flight test career ended in 1965, when he turned over leadership of the USAF test pilot school. He then completed transfer training to fly the McDonnell F-4 Phantom II.

Yeager was assigned to command the 405th Tactical Fighter Wing at Clark Air Base in the Philippines. The 405th TFW rotated its three aircraft squadrons in and out of Southeast Asia to conduct combat operations.

General Yeager would never consider commanding a combat unit unless he had flown his fair share of missions. To that aim, he flew 127 missions throughout the Vietnam War.

Following his appointment to Brigadier General in 1969, Yeager reported to Germany as the 17th Air Force’s vice commander. His final assignment before retiring was as Air Attaché at the US Embassy in Islamabad, Pakistan.

By any standard, Brigadier General Chuck Yeager’s Air Force career was significant on numerous levels. Serving 34 years and retiring as a Brigadier General is an impressive accomplishment, especially given that he did not attend college. I can only assume that he possessed exceptional flying abilities and was a natural leader.

What is the mystery behind the leading photograph at the top of this article?

Answer: This shot was taken at Edwards AFB in California in 1962. At the time, General Yeager was in charge of the Air Force test pilot school. It was housed at Edwards beside the USAF flight test center.

Yeager was holding an X-15 model and a photograph of the Bell X-1, in which he became the first man to break the sound barrier.

The photograph was intended to contrast what the flight test center was doing in 1947, when Yeager was a test pilot, with the advanced test programs done 15 years later in the North American X-15 rocket plane. The General flew Mach 2.44 in 1953, but not in the X-15.

He flew dozens and hundreds of planes, but the X-15 was not one of them. He has never flown the X-15 rocket plane. Yeager wanted to fly the X-15 but lacked the necessary certification. There were no flight test objectives that could be used to justify Yeager’s “spin around the block.”

Leave a Reply